What's next after the robotic revolution?

My long-winded attempt to think that through.

Hi there! This is my personal newsletter (Aaron’s Newsletter). I share thoughtful, authentic essays on the ideas shaping business, AI, and tech—so you can stay ahead, build smarter, and focus on what matters.

It’s 100% free to join, and you can get some fun rewards for getting your friends to join too.

I’m going to start with an assumption:

The robotic revolution happens.

Not humanoid Tesla butlers folding towels in your living room. I mean something deeper and less cinematic: robots that touch mines, farms, factories, roads, ports, warehouses. Robots that dig, move, cut, weld, ship, and assemble almost everything we use.

Today, the interesting question (to me) isn’t: “Will this happen?”

It’s: “Okay, what comes after that?”

If robots can create a surplus of almost everything,

What actually becomes scarce?

Who does the work that’s left?

Who gets the house next to the pretty waterfall?

Who spends their life maintaining robot fleets while other people mostly play?

And, underneath all of that: do we just rebuild the same old civilization? A civilization run by whoever has the “bigger stick,” or do we finally burn that pattern and try something else?

This essay is my long-winded attempt to think that through.

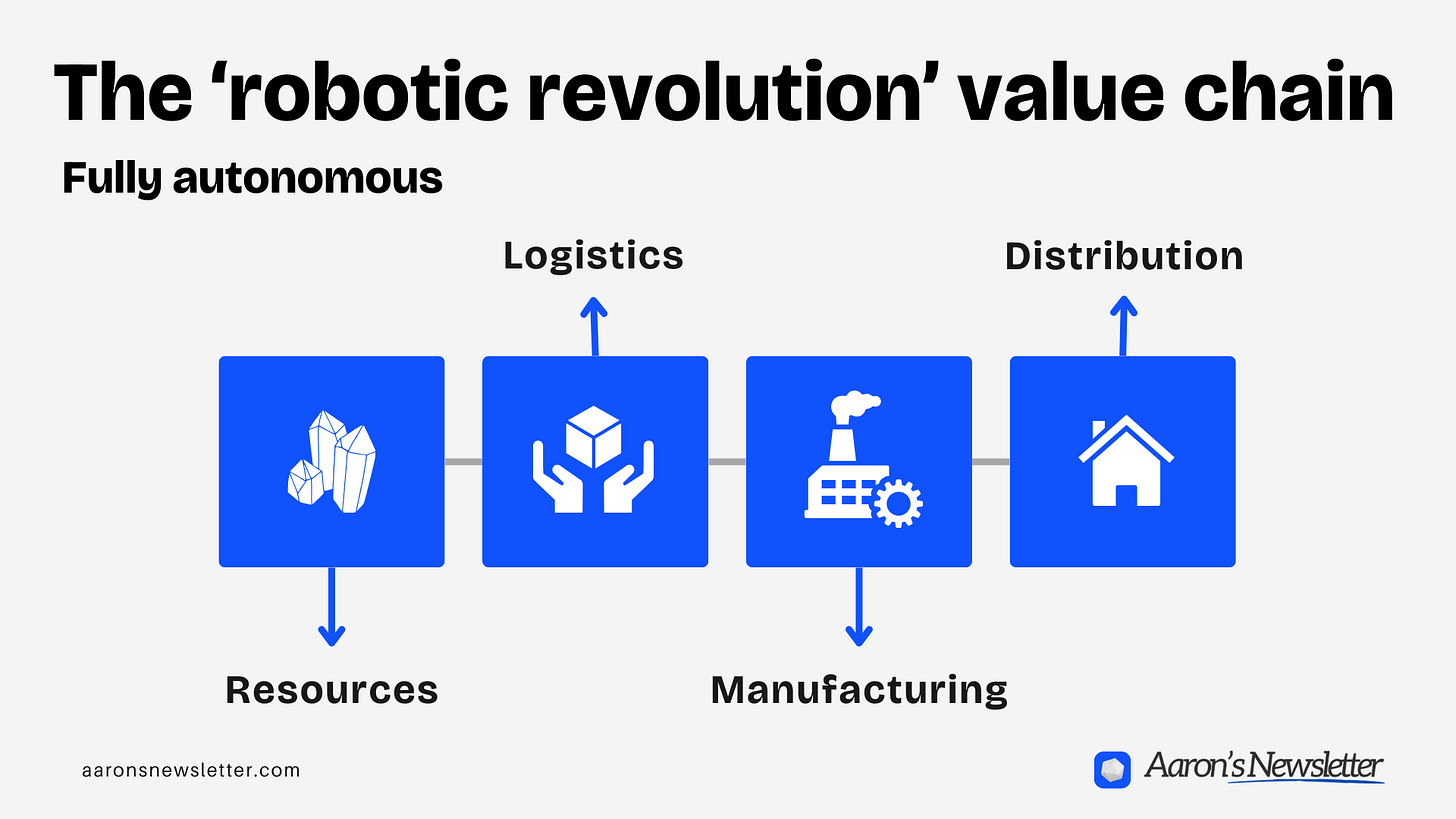

First, what is the ‘robotic revolution’

When I say “robotic revolution,” I’m not imagining some sudden sci-fi moment. I’m imagining a very boring, very powerful sequence.

It starts deep in the guts of the physical world.

First, automated resource gathering.

Robots in mines pulling metals from the ground.

Robots in forests harvesting timber.

Robots farming and fishing in the ocean.

Robots crawling across solar farms cleaning and repairing panels in the desert.

Then, logistics.

Self-driving trucks on the highways.

Automated ports that never sleep.

Drone fleets turning the sky into a delivery mesh.

Warehouses where the lights stay off because the robots don’t need them.

Then, manufacturing, construction, and fabrication.

Robotic arms on factory lines.

3D printers that extrude entire houses instead of trinkets.

Machines that cut, weld, assemble, and repair almost anything on command.

Finally, distribution.

Which is basically Amazon on god mode.

You press a button. The machines reshuffle matter. A thing appears at your door.

In my head, it collapses into a single chain:

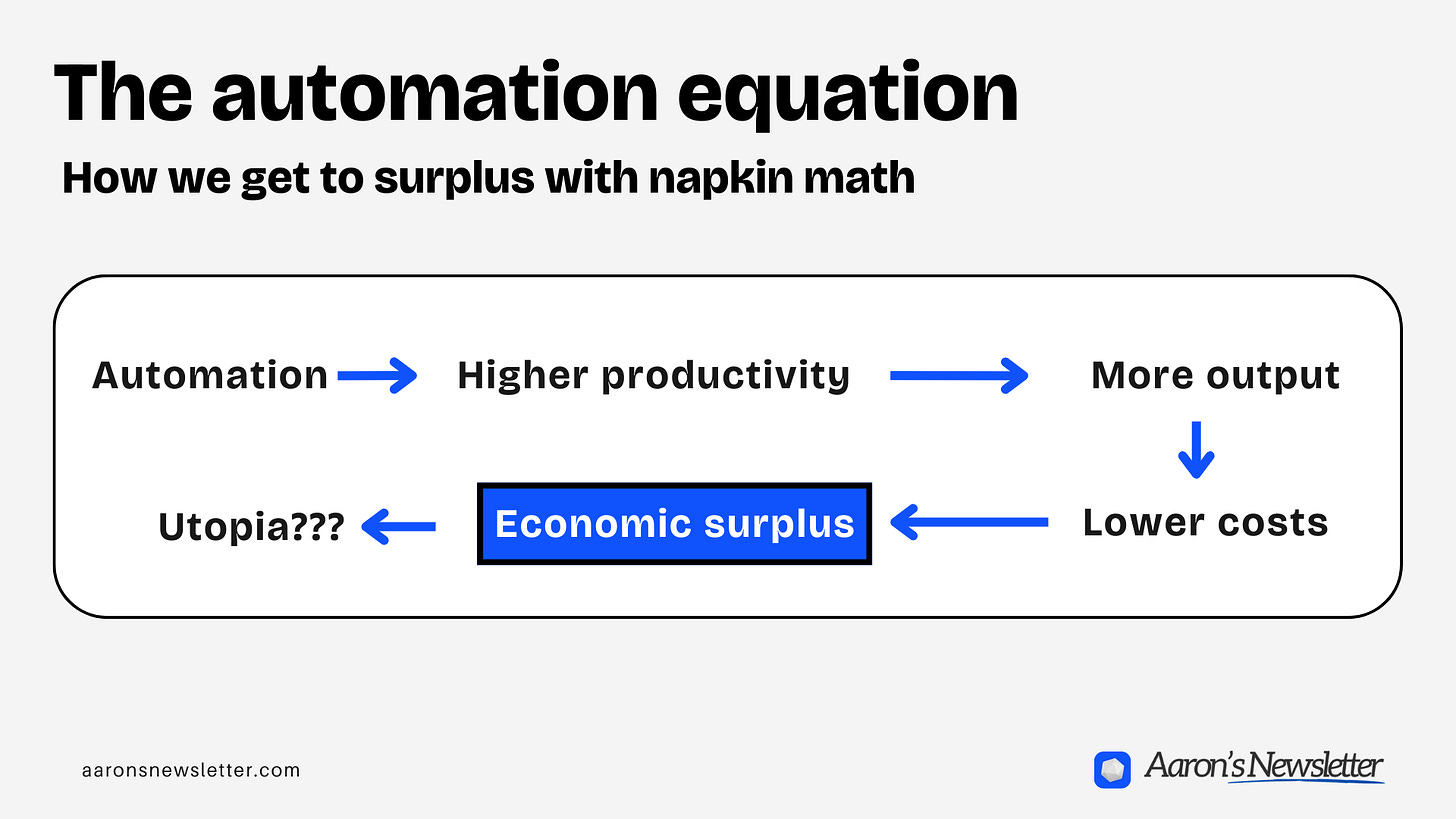

Automation → higher productivity → more output → lower cost → surplus.

Run that long enough and you end up in a weird place. A world where we can produce a surplus of almost everything people want.

Not infinite. Physics still exists. But enough that “we don’t have enough X” stops being the limiting story in a lot of categories.

That’s the glamorous version.

Underneath it is a much less glamorous world I think about a lot more.

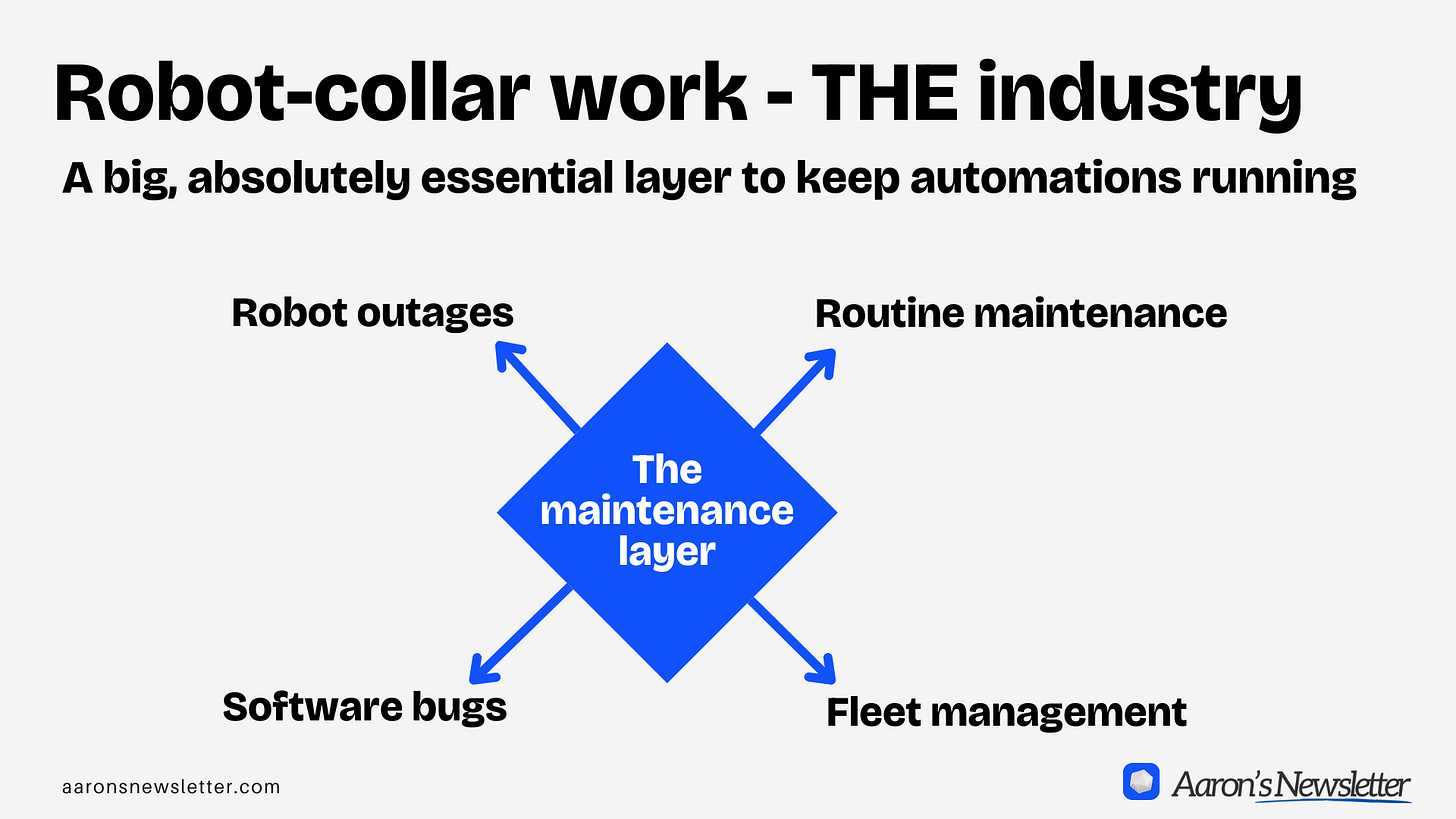

The ‘maintenance layer’

Under the shiny robotics machine, there’s a big, absolutely essential layer: maintenance.

A robotic civilization doesn’t run on its own. It runs on the maintenance layer.

Mining robots drift out of spec and need tune-ups.

Delivery drones chew through batteries.

Factory robots lose calibration.

Software accumulates bugs and needs updates.

Sensors get dirty.

Networks fall over if nobody’s watching.

The more we automate, the bigger this hidden layer becomes. You get a world of robots sitting on top of a much smaller world of humans who keep them alive.

My theory is this becomes one of the largest “industries” on the planet:

People who understand how to manage and maintain robotic fleets at scale.

People who live in dashboards and logs.

People who know when a weird pattern in sensor data is nothing, and when it’s about to shut down a port or a farm.

They’re not “blue collar” or “white collar” in the old sense.

They’re robot-collar.

And, that leads to a question I can’t shake: “What if most people don’t want to maintain and manage robot fleets?”

Because while this is happening, two other things are true:

Robots are slowly eating a lot of existing jobs.

Robots themselves are becoming the key assets in the system.

If robots are the new capital, then whoever owns and maintains the robots owns a huge chunk of the economy.

So, the robotic revolution isn’t just about new machines.

It’s about a new human stack sitting on top of those machines.

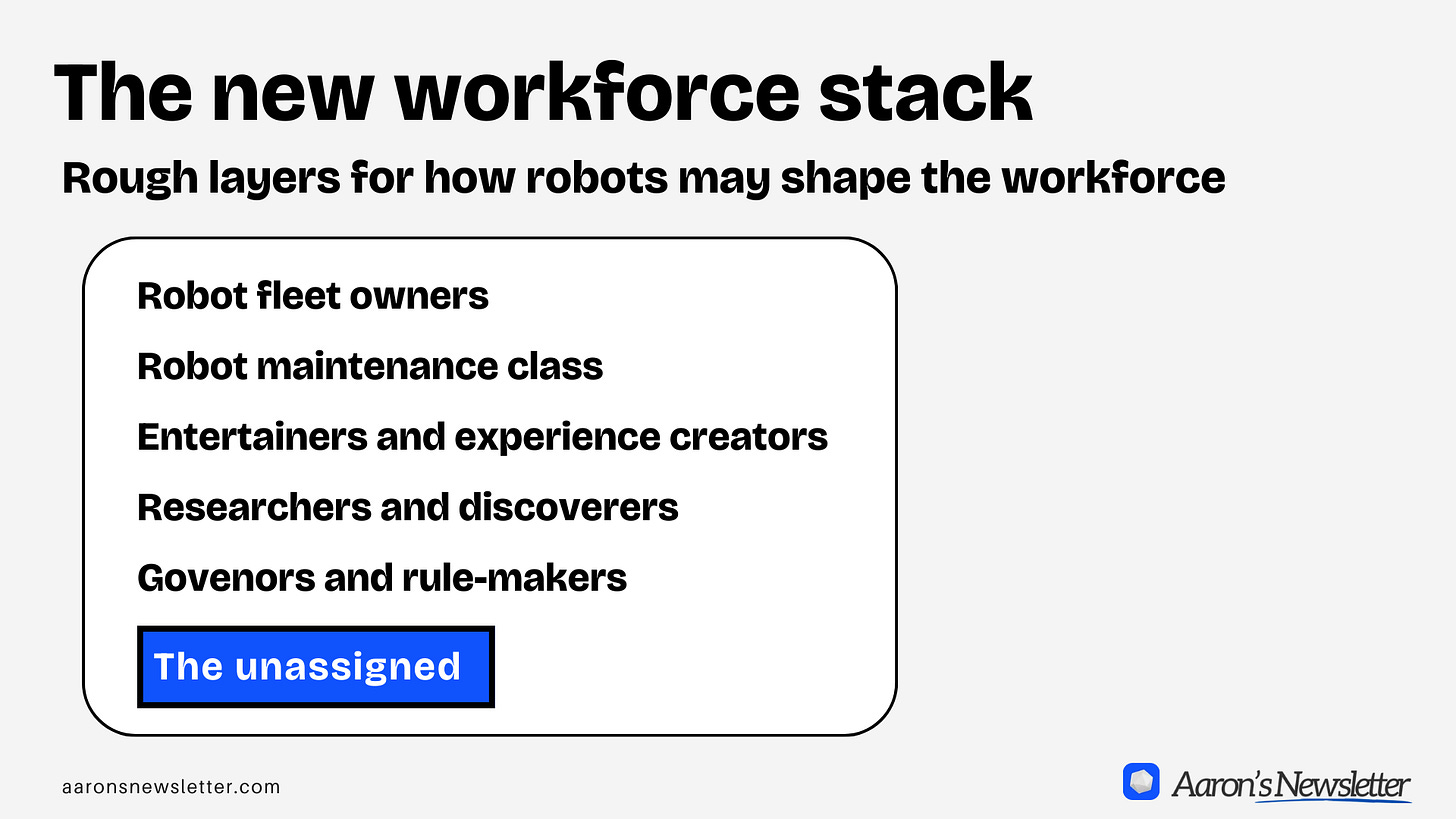

The robotic-era workforce stack

When I follow this through, I end up picturing society sorting into rough layers.

At the top, there are robot owners: the people and institutions that own the fleets and infrastructure. Let’s say the mines, fabs, warehouses, drone swarms, data centers, the software that coordinates all of it.

Under them are the robot stewards: the robot-collar class. Technicians, operators, systems engineers, fleet managers. People who keep the surplus machine running and decide what happens when things break.

Then there are entertainers and experience creators: streamers, creators, game designers, world builders, artists. As basic needs get cheaper, attention and experience get more valuable, and a lot of human energy flows there.

Alongside them, researchers and discoverers: people pushing the frontier of science and technology. Creating the new robots, new materials, new medicines, new models.

There are also governors and rule-makers: governments, regulators, boards, DAOs, whoever ends up setting the rules for critical infrastructure.

And finally, there’s a large, fuzzy category I think of as the unassigned: people who don’t have clear roles in this stack, or don’t want any of the ones on offer. They enjoy recreation art and are free to play, until they find how they want to contribute meaningfully.

This isn’t a rigid caste system. People move. Lines blur. But it exposes the part that feels most dangerous to me:

The surplus machine can scale almost without limit.

The number of high-agency roles cannot.

You get a structural mismatch:

There are way more people than there are meaningful, high-agency roles.

Whole industries get eaten by automation.

People who used to do physical or routine cognitive work wake up to find that the system can keep running just fine without them.

Ownership of robots and infrastructure concentrates unless something actively pushes against it.

A small group captures most of the upside.

The maintenance layer is vital, but narrow.

Not everyone can - or wants to - be a robotics tech or a fleet ops lead.

Which is totally fine.

But, we drift toward a pressure-building combination:

a relatively small owner class,

a thin but crucial steward class,

a hit-driven creator and entertainer world,

a small cluster of researchers and governors,

and a very large unassigned population the system doesn’t really need to function.

That creates pressure in three directions at once:

Moral pressure: If the surplus machine can provide enough for everyone, what does it say about us if we let large groups live in misery?

Political pressure: ff a tiny group owns the robots and everyone else has no stake, that isn’t just inequality. It’s instability.

Psychological pressure: What happens when millions of people quietly realize: “The system doesn’t actually need me to survive. I’m optional.”

At that point, minimum living standards stop being a utopian thought experiment. They start to look like basic risk management.

Minimum living standards, and utopian thoughts

Once I accept two premises:

Robots can produce far more than our basic needs.

There are fewer “needed” roles than people who want to matter.

…minimum living standards change shape.

It’s no longer: “Wouldn’t it be nice if everyone had enough?”

It becomes: “We might have to guarantee that everyone has enough, or this whole thing tears itself apart.”

In a robotic world, “enough” starts to look like:

Safe, clean, comfortable housing

Enough food and water

Basic healthcare

Education and connectivity

Reliable energy and infrastructure

The surplus machine plus the maintenance layer make that logistically and economically possible in a way previous civilizations could only fantasize about. You don’t need everyone in fields or factories to justify giving them a roof and a meal. The robots already did that work.

So, minimum living standards become three things at once:

A moral response to abundance (“If we can, why wouldn’t we?”)

A political pressure valve (“If we don’t, this blows up.”)

A psychological baseline (“You exist, therefore you will not starve.”)

And once that floor is in place, a huge door swings open.

If fewer people are needed for survival work, more people are available for everything else. Less time grinding for rent means more time available for play, art, and exploration.

You can imagine a civilization where:

Entertainment and recreation grow into the largest “industry” by time spent

People spend most of their days in games, virtual worlds, creative projects, and communities

Housing starts to drift from mere shelter toward art and self-expression, because robots can build almost anything

On paper, it starts to look like a second renaissance.

If you can print any structure you can describe, your home becomes a 3D self-portrait of your family: your taste, your values, your weirdness cast into walls and geometry. Neighborhoods start to feel less like grid plans and more like collaborative art projects.

Robots can make housing cheap. They can make “good enough” housing abundant.

While that is true, robots cannot print more coastline, more mountain ridges, more perfect climates, or more slots in the handful of cities where everyone wants to be.

So, I expect humans will still be able to find stuff to fight about.

The house by the waterfall & other dumb things humans would fight over.

Minimum living standards might solve survival. They don’t solve the things people really fight over.

Even in a robotic surplus world, some things stay structurally scarce:

Location. The house by the waterfall. The best neighborhoods. The cities with the strongest networks.

“Caviar-level” goods. Stuff that is rare by nature or rare by design—unique environments, limited experiences, high-touch services, truly scarce ingredients.

Attention and status. You can’t give everyone the same recognition, influence, or say. Not everyone can sit in the key decision-making rooms.

How do we solve questions like:

Who gets the bigger house?

Who gets the house by the waterfall?

Who gets the rare experiences, the caviar, the best roles?

Who gets to feel like their work actually matters?

If the waterfall house exists, how can it be “right” that one person or one family controls it? Especially, in a society where we already can supply the minimum living standards to everyone.

And once you see that, a very natural thought appears:

If a world like this is possible, and it feels unfair that some people get the best houses and best land:

Why not just go all the way?

If it’s unfair that one person gets the house by the waterfall, the instinctive move is: then nobody should “own” the waterfall at all.

Since, there will always be a finite number of truly prime locations & scare resouces.

Why not:

get rid of private property,

get rid of money,

share everything,

and let the surplus machine provide for everyone equally?

Before getting rid of all private right, lets go back in history…

In early human societies, you could say things were more “communal” in some sense—small bands, tight tribes, shared labor.

But the incentives were very different from what people imagine in a robotic surplus world.

There was always a minimum amount of labor required to survive. Food didn’t appear because someone pushed a button. If enough people slacked off, the group went hungry, got cold, or became vulnerable to attack.

Contribution wasn’t a side quest; it was the price of admission.

If you didn’t contribute, you weren’t just seen as “lazy.”

You were a risk.

Someone who ate from the pot without helping fill it. Someone who consumed protection without helping provide it.

And the enforcement wasn’t abstract. It was social and visceral:

You could be shamed, mocked, or pushed to the edge of the group.

You could be the last to eat, the least protected, the one nobody rushed to help.

In the extreme, you could be driven out completely.

Surviving alone was hard enough that very few people wanted to roll that dice.

Being cast out wasn’t just a bad vibe; it was often a death sentence.

Even groups of “outcasts” who banded together still had to do hard, physical, coordinated work to meet basic needs. There was no robot safety net waiting to catch them.

So older communal-ish societies had a brutal but simple logic:

You needed the group to survive.

The group needed you to pull your weight.

Social pressure and the threat of exclusion kept most people in line.

Now, compare that to a robotic surplus world with minimum living standards.

If the surplus machine and maintenance layer guarantee that you:

won’t starve,

won’t be homeless,

can get basic healthcare,

and can access some baseline of information and entertainment,

Te cost of opting out is very different.

You can, in principle:

live alone or in a small pod without your neighbors needing you,

refuse to contribute anything essential and still have your basic needs met,

retreat into virtual worlds or small circles and never really be socially punished for it

The old communal enforcement mechanism—“help us or you might not eat”—stops working. The group needs you less, and you need the group less.

That’s liberating in one sense. It means people aren’t forced into survival labor just to be tolerated.

But it’s also dangerous, because once that social glue weakens, a lot of “communal utopia” assumptions break. You can’t rely on the same peer pressure and shared risk that made older tribes function.

If you try to copy their “we all share everything” aesthetic in a world where individuals can survive alone on the floor, you get a very different beast.

And that’s where the modern version of the dream shows up: “We’ll just scale that communal feeling up to everyone. No private ownership, no money, shared everything, robots & our shared work will handle the rest.”

However, it gets weird.

Even if robots do most production, the system still depends on a maintenance layer of humans.

So, if you build a world where opting out is socially acceptable and materially safe, you create a mismatch.

Some people keep civilization running, while others can live comfortably without contributing anything essential.

That’s not a moral failing. It’s just incentives. But it does create an emotional and political fault line.

The robot-stewards start to feel like the only adults in the room. The opt-outs start to feel judged for taking a deal the system itself offered.

And once that resentment shows up, “shared everything” stops feeling like a utopia and starts feeling like: “Wait… why am I maintaining the machine while you mostly play?”

At that scale, with that level of complexity, you end up in something we’ve already experimented with…

And, historically, it doesn’t end up well for those who gave up their power to the stewards.

The risk of robotic communism and what I call the FINAL stick

If you take the “no money, no property, all shared” fantasy seriously and scale it past a small tribe, you end up rhyming with a very old idea:

Communism.

Not the abstract ideal where everyone is enlightened and altruistic, but the real, historical pattern:

common ownership of productive assets,

centralized planning of who gets what,

an official promise of equality.

On paper, communism sounds a lot like the robotic surplus dream:

The people own the means of production.

Everyone gets the basics.

We produce according to ability and distribute according to need.

However, historically, a few stubborn patterns kept showing up in communism:

Power concentrated around whoever controlled planning and enforcement.

Incentives blurred, because the difference between doing your best and phoning it in got softer at the margin.

Information got distorted; people told the plan what it wanted to hear, not what was true on the ground.

Black markets sprang up to route around shortages, rigidity, and bad decisions.

Instead of a flat utopia, you got:

an elite with real control over resources and force, and

a mass of “equal” citizens who lived with scarcity and very little say.

Now drop robots into that picture. Call it “robotic communism”:

All the robots, fleets, infrastructure, and factories are “owned by the people,” which in practice means by a central state or coordinating body. There’s no meaningful private ownership of robot fleets or logistics.

There’s an official promise: the surplus machine belongs to everyone; everyone gets their share.

At first, it might look incredible. Robots harvest, build, cook, deliver. Everyone gets standardized housing, food, healthcare, connectivity. You tap a screen and things show up.

But, all the old failure modes are still there. It’s just running on top of automated infrastructure instead of human labor.

Someone still decides:

which regions get the newest robots and best infrastructure,

who gets upgraded housing and who stays in standard blocks,

which maintenance issues are treated as urgent and which are quietly ignored,

who gets access to scarce locations, special experiences, and travel.

If they get those decisions wrong, the system doesn’t just get a bit unfair. It gets brittle. Logistics fail. Regions lose power or food. Entire supply chains crumble because some central planner or local official made bad calls.

And on top of that, robotics supercharges the “bigger stick” problem.

In older eras, the bigger stick belonged to whoever controlled land, food; and, most importantly, the military.

For discussion on the the “bigger stick” today, watch this debate with John Mearsheimer and Jeffrey Sachs:

In a robotic communism scenario, one relatively small organization can control:

the robot fleets that produce food, housing, and energy,

the networks everyone depends on,

and the robotic enforcement stack—drones, surveillance, automated policing, maybe even autonomous weapons.

That’s a level of consolidated leverage we’ve never had before.

You don’t need a bloated state to be terrifying. You just need a tight, technical group with the keys to the surplus machine and the enforcement machine at the same time.

On the surface, it’s “efficiency” and “equality.”

Underneath, it’s soft totalitarianism with perfect enforcement, or creeping chaos when the machine starts to fail.

Either way, it’s not the second renaissance we were hoping for.

That’s why I DON’T think the path forward is: “Abolish property, abolish money, centralize the robots, and trust the planner.”

We probably do want minimum living standards in a robotic world.

We probably don’t want to layer full-blown communism on top of that.

So, the question shifts… how do we build a system on top of minimum living standards that:

stays fair to the people actually doing the work,

lets people climb above the floor,

doesn’t drift into robotic communism,

and doesn’t congeal into robot feudalism?

That’s where land, money, and entrepreneurship come back into the story.

So I don’t think the answer is to erase ownership and pretend nobody owns anything. I think the answer looks more like:

Keep property and markets, but run them on top of a robotic surplus that guarantees a floor.

Nobody should be homeless or starving in a world that can trivially prevent it. Nobody should be locked out of basic healthcare, education, or connectivity. The surplus machine can and should provide that.

But above that floor, there is still a game. Some people will end up with better houses, better locations, better experiences.

The question is: what game are they playing to get there?

Capitalism with a floor. Why I believe currency must survive.

It’s tempting to imagine that if robots make everything cheap enough, money disappears.

I don’t think that’s how it plays out.

As long as desire exceeds supply for some slice of reality, you need a way to compare tradeoffs, allocate access, and keep score. That’s what money—or whatever replaces it—is.

It might not look like dollars in a bank account. It might look like tokens, reputation-weighted access, local currencies, or something we don’t have a name for yet. But some kind of currency is going to survive.

Above a certain floor, the economy stops being about survival and starts being about status, agency, and contribution.

You don’t work just to eat. You work to move to a nicer location, to unlock better experiences, to have more leverage over what gets built, to have more say in how things run, to feel needed.

That’s what I mean by ‘capitalism with a floor:

The floor is guaranteed by robots + stewards.

On top of that, there is still a game where you can earn more than the minimum.

The key design choice is this: If you want more than the minimum, your best path up should be to make the world better for other people.

Not to grab the bigger stick. Not to exploit obscure leaks in the rules. But to actually build things, services, communities, and experiences that improve life.

That’s where entrepreneurship comes in.

Entrepreneurship and the productized self

In a capitalism-with-a-floor world, entrepreneurship becomes one of the main ways an individual can:

earn more than the minimum

access better locations and experiences

gain more agency and say

The clean version of this is simple: you move above the floor by creating value for others.

Entrepreneurship here doesn’t just mean “start a SaaS company and raise a seed round.” It can look like:

starting a cooperative that manages and maintains robotic fleets more safely and more fairly

designing new forms of housing and shared spaces that people genuinely want to live in

building tools and apprenticeship paths that help displaced workers transition into stewardship or creative work

creating games, worlds, and cultural products that actually enrich people’s lives instead of just farming their attention

launching new kinds of communities, education systems, or local governance models that help people live better together

Money (or whatever replaces it) becomes a way of routing resources toward people and projects that are actually useful, not just politically connected.

At the same time, the productization of the self accelerates.

Like it or not, each person starts to look more like a portfolio:

of projects they’ve shipped

of systems they’ve improved

of people they’ve helped

Your real “asset” isn’t just your account balance. It’s your track record.

What did you build?

Who did you help?

What got safer, richer, or more interesting because you were involved?

Who trusts you enough to follow you, fund you, or work with you?

Right now, we approximate that with views, likes, and follower counts.

In a healthier version of a robotic future, it tilts more toward: show me what you actually did.

That still doesn’t guarantee a good future.

Because even with:

a high floor

entrepreneurship-as-contribution

reputation as a key asset

There’s still a gravitational pull toward consolidation.

Rich people buy more land. Robot owners buy more robots. Stewardship slowly gets captured by a small technical priesthood. The bigger stick starts to reform itself out of land, fleets, and enforcement systems.

If we’re not careful, “capitalism with a floor” turns into robot feudalism with better UX.

So the ultimate question becomes: How do we keep the bigger stick from just reassembling itself?

How to burn the ‘bigger stick’

For most of history, the bigger stick has been some mix of:

land

resources

and the capacity for violence or exclusion

Feudal lords controlled land. Peasants worked that land to survive. If they didn’t comply, they could be pushed off, starved, punished.

Later, industrial states fought over territory, coal, oil, and factories. Control the resource base, control the ports, control the army—you control the future.

The pattern tends to rhyme:

Control the essentials: land, resources, production, enforcement.

Use threats or exclusion to enforce your position.

Call the result “order.”

Robots add a new layer to that pattern. The essentials are no longer just land and human labor. They’re:

land

robot fleets

critical infrastructure

and, potentially, robotic enforcement (drones, sensors, automated security)

If we design this badly, one entity can grab all of that and hold a robotic bigger stick so large it makes past empires look quaint.

When I say I want to “burn the bigger stick,” I don’t mean “no one should have power.” We still need coordination, leadership, and sometimes force.

I mean we should stop building systems where one small group can own the land, the robots, and the enforcement stack and call that “for the common good.”

Ownership will still matter. Money will still matter. Status will still exist.

Burning the bigger stick, to me, means:

making it much harder for power to fully centralize

tying status to contribution rather than raw extraction

and giving more people real, legible paths into ownership and stewardship

That’s where design choices actually matter.

The middle ground in ‘robo-capitalism’

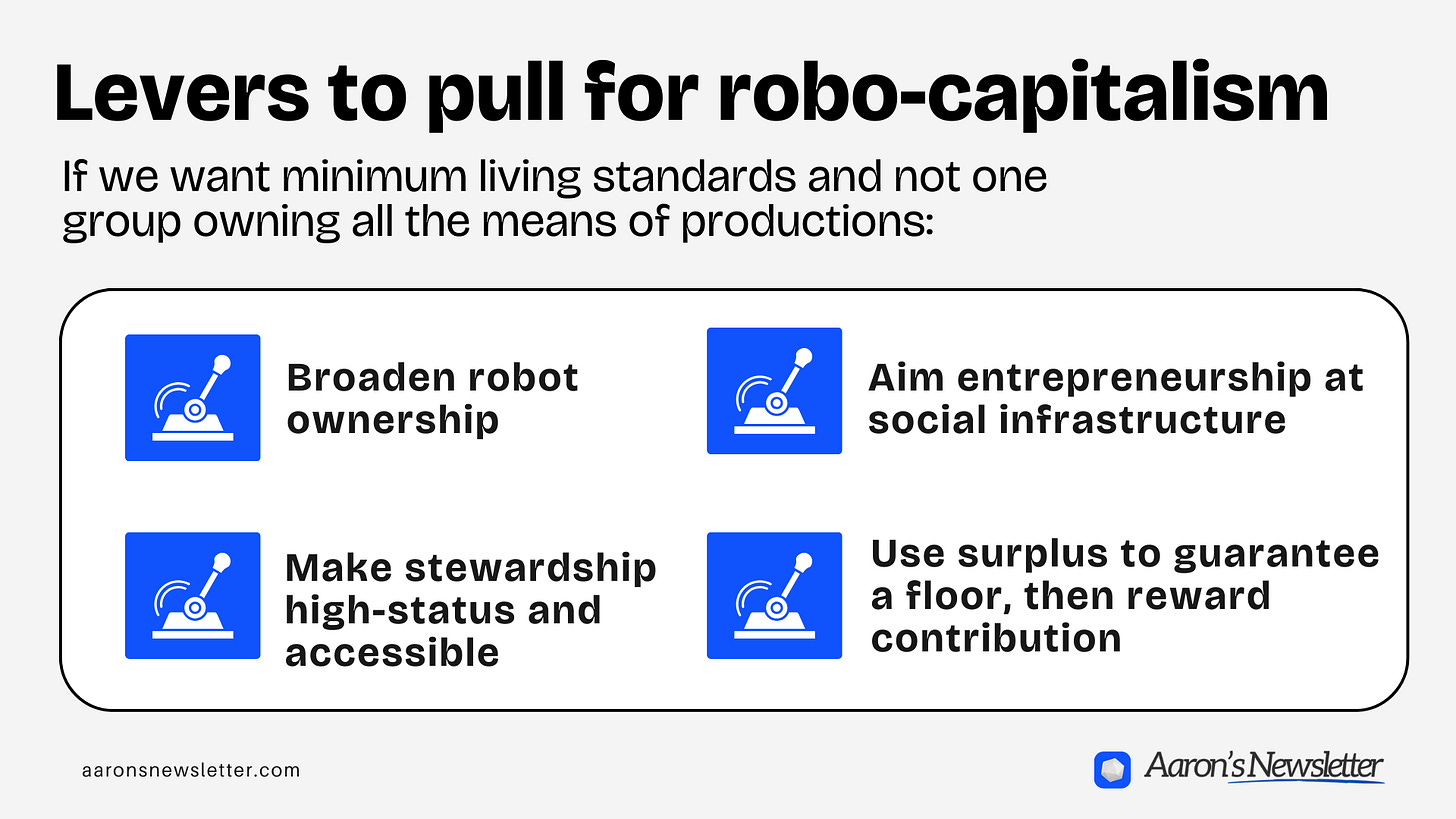

I don’t have a master blueprint. But if we want:

minimum living standards

capitalism above the floor

and less “one group with a giant robotic stick” risk

then a few levers look especially important.

Broaden robot ownership.

If robots are the new capital, then ownership is power. We probably want more shared fleets, co-ops, and public/commons infrastructure, not total centralization. It doesn’t have to be perfectly equal. It just doesn’t have to be feudal.

Make stewardship high-status and accessible.

Robot-collar work should feel like stewardship of civilization, not backend drudgery. That means cheap, accessible education and tools; clear paths in; and real autonomy and upside. “I keep the robots alive” should sound like something you’re proud to say.

Use surplus to guarantee a floor, then reward contribution.

Let the surplus machine fund minimum living standards. Above that, tie additional rewards to meaningful contribution: building infrastructure, healing and teaching, maintaining systems, creating art and experiences, starting communities, protecting ecosystems, helping displaced workers find new roles.

Aim entrepreneurship at social infrastructure.

We can nudge entrepreneurship away from pure attention extraction and toward building the scaffolding of a good society: new living models, new education and training systems, new governance experiments, better ways to share land and surplus.

Shift culture: who we admire.

We can’t legislate culture, but we can choose what we celebrate. We can admire people with the biggest fleets and fanciest houses—or the people who use surplus to expand other people’s agency and meaning. Those choices compound.

None of this guarantees success. But it does bend the game away from “whoever has the bigger stick wins” and toward a more interesting question:

Who builds the most useful systems?

Who stewards the most important infrastructure?

Who expands the set of lives that feel worth living?

What’s next is NOT set in stone. Don’t mess it up.

So, what’s next after the robotic revolution? Not just more robots. Not just cheaper stuff.

What comes next is a set of choices about:

how we handle the mismatch between surplus and meaningful roles

how we deal with old scarcity (land) and new capital (robots)

how we treat the people who maintain the machine versus the people who mostly play on top of it

whether we keep running civilization on the bigger stick—or decide to burn that pattern and build something else

Robots can give us almost anything:

Housing as art.

Time to play.

A surplus of goods no other generation has ever seen.

What they can’t do is answer the hard part:

Who gets the house by the waterfall.

Who carries the burden of maintenance.

What we think is worth competing for.

What we owe to the people the system doesn’t strictly “need.”

That part is still our job.

-Aaron

More from me:

Become a master pitcher & inventor – the fun way

Products: The Card Game: Get my game where ‘Shark Tank’ meets Apples to Apples.

Share the newsletter and get rewards

Refer friends for rewards: Get cool rewards (like my card game) for referring people to my newsletter. Check out where you stand on the leaderboard.